In my last blog, I talked about Xcential’s long history working with change management as it applies to legislation and my personal history working in the subject in other fields.

In this blog, I’m going to focus in on change management as it is used in Akoma Ntoso. I’m going to use, as my example, a piece of legislation from the California Legislature. As I implemented the drafting system used in Sacramento (long before Akoma Ntoso), I have a bit of a unique ability to understand how change management is practiced there.

First of all, we need to introduce some Akoma Ntoso terminology. In Akoma Ntoso, a change is known as a modification. There are two primary types of modifcations:

- Active modifications — modifications in which one document makes to another document.

- Passive modifications — modifications being proposed within the same document.

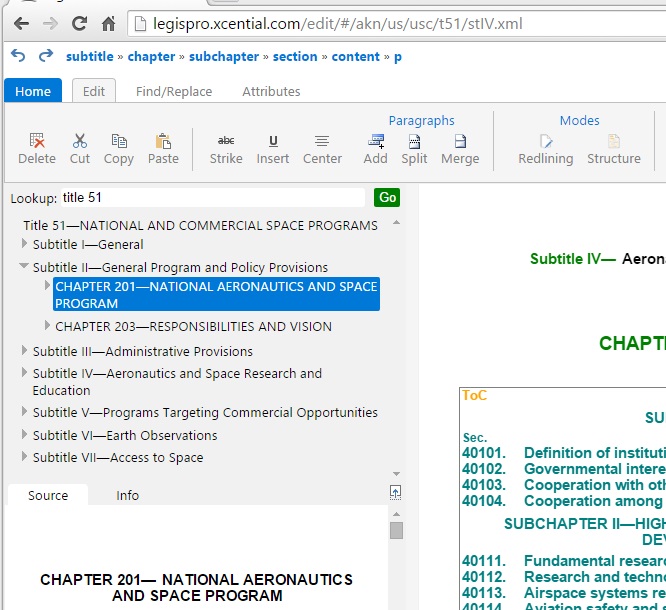

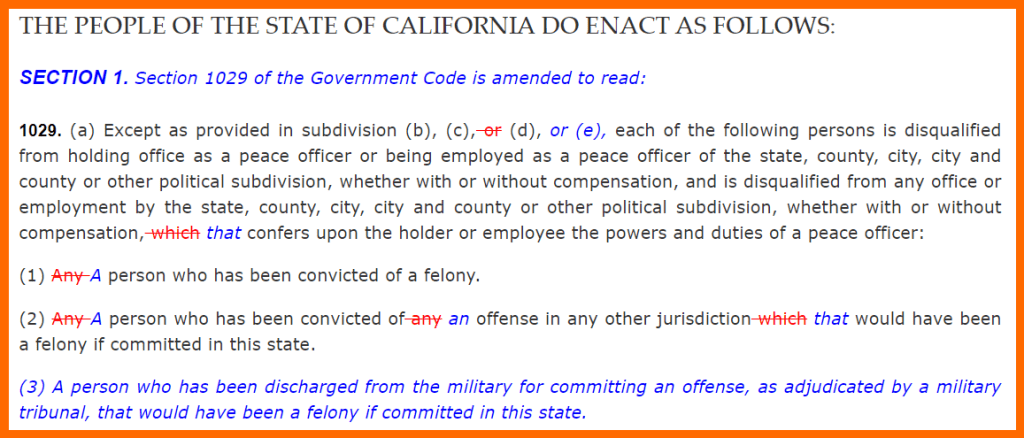

The snippet I am using for example is a cropped section from AB17 from the current session:

In California, many changes are shown using what they call redlining — or you may know as track changes. However, it would be a mistake to interpret them literally as you would in a word processor — a bit of the reason why it’s difficult to apply a word processor to the task of managing legislative changes.

In the snippet above, there are a number of things going on. Obviously, Section 1 of AB17 is amending Section 1029 of the Government Code. Because California, like most U.S. states, only allows their codes or statutes to be amended-in-full. The entire section must be restated with the amended language in the text. This is a transparency measure to make it more clear exactly how the law is being changed. The U.S. Congress does not have this requirement and Federal laws may use the cut-and-bite approach where changes can be hidden in simple word modifications.

Another thing I can tell right away is that this is an amended bill — it is not the bill as it was introduced. I will explain how I can tell this in a bit.

From a markup standpoint, there are three types of changes in this document. Only two of these three types are handled by Akoma Ntoso:

- As I already stated, this bill is amending the Government Code by replacing Section 1029 with new wording. This is an active change in Akoma Ntoso of type insertion.

- Less obvious, but Section 1 of AB17 is an addition to the bill as originally introduced. I can tell this because the first line of Section 1, known in California as the action line, is shown in italic (and in blue which is a convention I introduced). The oddity here is that while the section number and the action line are shown as an insertion, the quoted structure (an Akoma Ntoso term), is not shown as inserted. The addition of this section to the original bill is a passive change of type insertion.

- Within the text of the new proposed wording for Section 1029, you can also see various insertions and deletions. Here, you have to be very careful in interpreting the changes being shown. Because this is the first appearance of this amending section in a version of AB17, the insertions and deletions shown reflect proposed changes to the current wording of Section 1029. In this case, these changes are informational and are neither an active nor passive change. Had these changes been shown in a section of the bill that had already appeared in a previous version of AB17, these these changes would be showing proposed changes to the wording in the bill (not necessarily to the law) and they would be considered to be passive changes.

The rules are even more complex. Had section 1 been adding a section to the Government Code, then the quoted text being added would be shown as an insertion (but only in the first version of the bill that showed the addition). Even more complex, had the Section 1 been repealing a section of the Government Code, then the quoted text being repealed would be shown as a deletion (and would be omitted from subsequent versions of the bill). This last case is particularly confusing to the uninitiated because the passive modification of type insert is adding an active modification of type repeal. The redlining shows the insertion as an italic insertion of the action line while the repeal is being shown as a stricken deletion of the quoted structure.

The lesson here is that track changes, as we may have learned them in a word processor, aren’t as literal as they are in a word processor. There is a lot of subtle meaning encoded into the representation of changes shown in the document. Being able to control track changes in very complex ways is one of the challenges of building a system for managing legislative changes.