LegisPro Sunrise is almost done!. It has taken longer than we had hoped it would, but we are finally getting ready to begin limited distribution of LegisPro Sunrise, our productised implementation of our LegisPro drafting and amending tools for legislation and regulations. If you are interested in participating in our early release program, please contact us at info@xcential.com. If you already signed up, we will be contacting you shortly.

LegisPro Sunrise is a desktop implementation of our web-based drafting and amending products. It uses Electron from GitHub, built from Google’s Chromium project, to bundle all the features we offer, both the client and server sides into a single easy-to-manage desktop application with an installer having auto-update facilities. Right now, the Windows platform is supported, but MacOS and Linux support will be added if the demand is there. You may have already used other Electron applications – Slack, Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code, WordPress, some editions of Skype, and hundreds of other applications now use this innovative new application framework.

Other versions

In addition to the Sunrise edition, we offer LegisPro in customised FastTrack implementations of the LegisPro product or as fully bespoke Enterprise implementations where the individual components can be mixed and matched in many different ways.

In addition to the Sunrise edition, we offer LegisPro in customised FastTrack implementations of the LegisPro product or as fully bespoke Enterprise implementations where the individual components can be mixed and matched in many different ways.

Akoma Ntoso model

LegisPro Sunrise comes with a default Akoma Ntoso-based document model that implements the basic constructs seen in many parliaments and legislatures around the world that derive from the Westminster parliamentary traditions.

Document models implementing other parliamentary or regulatory traditions such as those found in many of the U.S. states, in Europe, and in other parts of the world can also be developed using Akoma Ntoso, USLM, or any other well-designed XML legislative schema.

Drafting & Amending

Our focus is on the drafting and amending aspects of the parliamentary process. By taking a digital-first approach to the process, we are able to offer many innovative features that improve and automate the process. Included out of the box is what we call amendments in context where amendment documents are extracted from changes recorded in a target document. Other features can be added through an extensive plugin mechanism.

Basic features

Ease-of-use

While offering sophisticated drafting capabilities for legislative and regulatory documents, LegisPro Sunrise is designed to provide the familiarity and ease-of-use of a word processor. Where it differs is in what happens under the covers. Rather than drafting using a general purpose document model and using styles and formatting to try to capture the semantics, we directly capture the semantic structure of the document in the XML. But don’t worry, as a drafter, you don’t need to know about the underlying XML – that is something for the software developers to worry about.

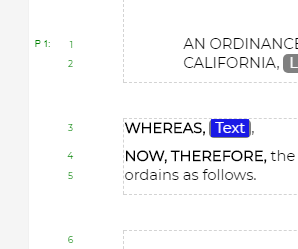

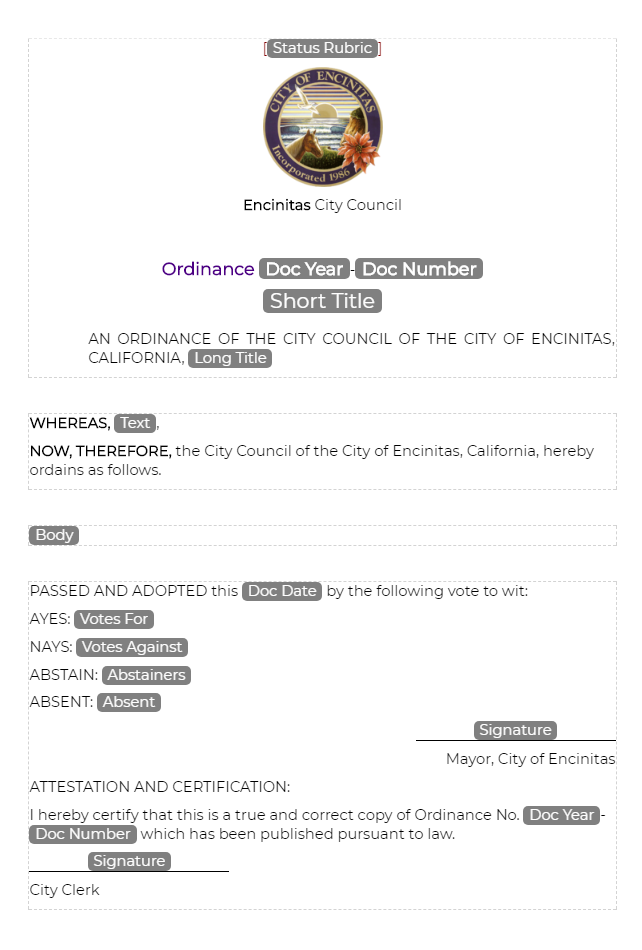

Templates

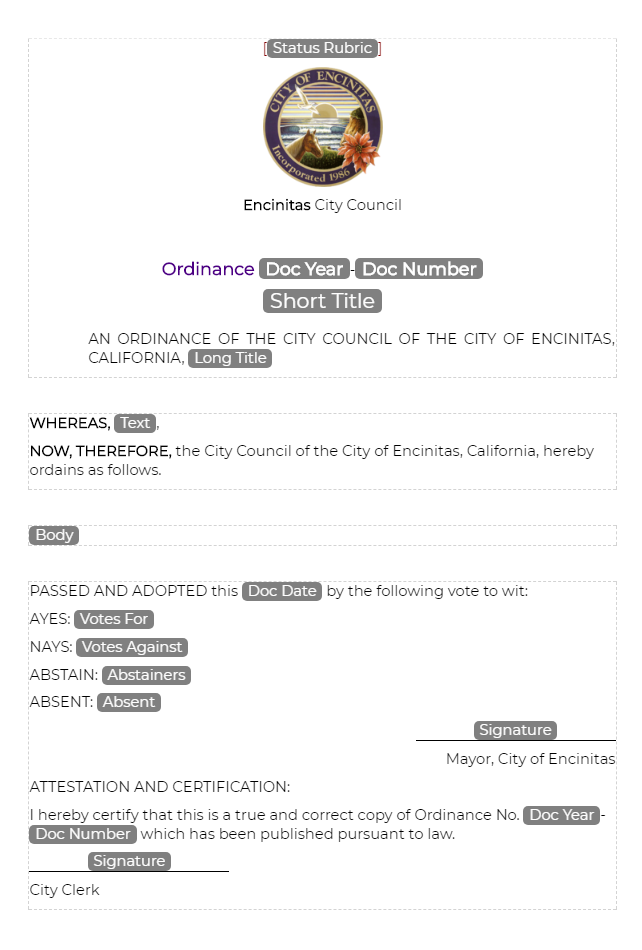

Templates allow the boilerplate structure of a document to be instantiated when creating a new document. Out-of-the-box, we are providing generic templates for bills, acts, amendments, amendment lists, and a few other document types.

Templates allow the boilerplate structure of a document to be instantiated when creating a new document. Out-of-the-box, we are providing generic templates for bills, acts, amendments, amendment lists, and a few other document types.

In addition to document templates, component templates can be specified or are synthesized when necessary to be used as parts when constructing a document.

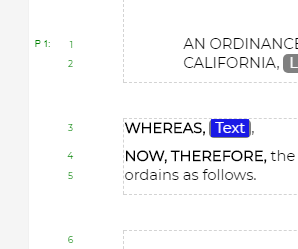

For both document and component templates, placeholders are used to highlight area where text needs to be provided.

Upload/Download

As a result to our digital-first focus, we manage legislation as information rather than as paper. This distinction is important – the information is held in XML repositories (a form of a database) where we can query, extract, and update provisions at any level of granularity, not just at the document level. However, to allow for the migration from a paper-oriented to a digital first world, we do provide upload and download facilities.

Undo/Redo

As with any good document editor, unlimited undo and redo is supported – going back to the start of the editing session.

As with any good document editor, unlimited undo and redo is supported – going back to the start of the editing session.

Auto-Recovery

Should something go wrong during an editing session and the editor closes, an auto-recovery feature is provided to restore your document to the state the document was at, or close to it, when the editor closed.

Contextual Insert Lists

We provide a directed or “correct-by-construction” approach to drafting. What this means is that the edit commands are driven by an underlying document model that is defined to enforce the drafting conventions. Wherever the cursor is in the document, or whatever is selected, the editor knows what can be done and offers lists of available documents components that can either be inserted at the cursor or around the current selection.

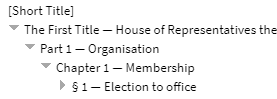

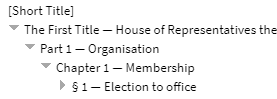

Hierarchy

Document hierarchies form an important part of any legislative or regulatory document. Sometimes the hierarchy is rigid and sometimes it can be quite flexible, but either way, we can support it. The Sunrise edition supports the hierarchy Title > Part > Chapter > Article > Section > Subsection > Paragraph > Subparagraph out of the box, where any level is optional. In addition, we provide support for cross headings which act as dividers rather than hierarchy in the document. Customised versions of LegisPro can support whatever hierarchy you need — to any degree of enforcement. A configurable promote/demote mechanism allows any level to be morphed into other levels up and down the hierarchy.

Large document support

Rule-making documents can be very large, particular when we are talking about codes. LegisPro supports large documents in a number of ways. First, the architecture is designed to take advantage of the inherent scalability of modern web browsing technology. Second, we support the portion mechanism of Akoma Ntoso to allow portions of documents, at any provision level, to be edited alone. A hierarchical locking mechanism allows different portions to be edited by different people simultaneously.

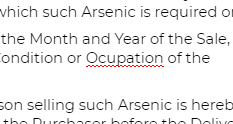

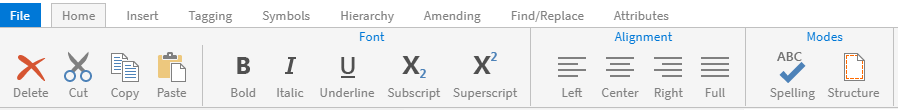

Spelling Checker

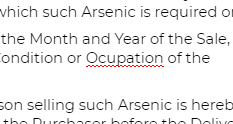

Checking spelling is an important part of any document editor and we have a solution – working with a third-party service we have tightly integrated with in order to give a rich and comprehensive solution. Familiar red underline markers show potential misspellings. A context menu provides alternative spellings or you can add the word to a custom dictionary.

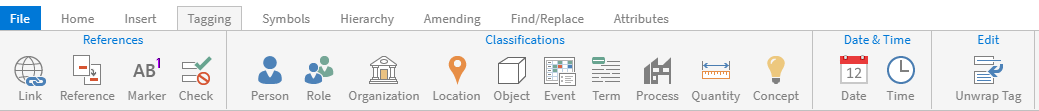

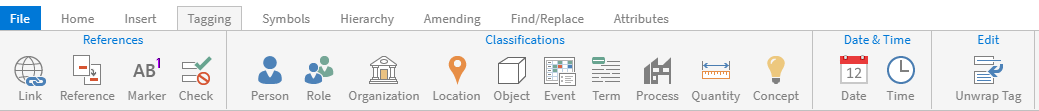

Tagging support

Beyond basic drafting, tagging of people, places, or things referred to in the document is something for which we have found a surprising amount of interest. Akoma Ntoso provides rich support for ontologies and we build upon this to allow numerous items to be tagged. In our FastTrack and Enterprise solutions we also offer auto-tagging technologies to go with the manual tagging capabilities of LegisPro sunrise.

Document Bar

The document bar at the top of the application provides access to a number of facilities of the editor including undo/redo, selectable breadcrumbs showing your location in the document, and various mode indicators which reflect the current editing state of the editor.

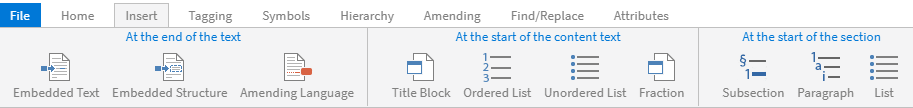

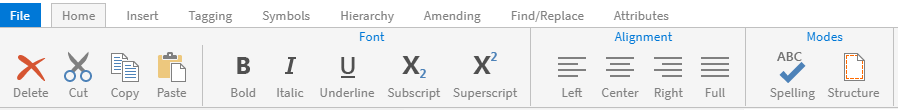

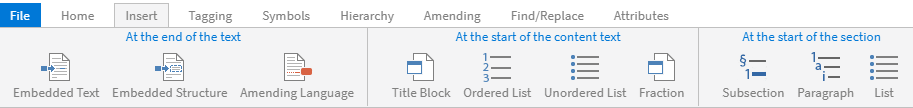

Command Ribbons and Context Menus

Command ribbons and context menus are how you access the various commands available in the editor. Some of the ribbons and menus are dynamic and change to reflect the location the cursor or selection is at in the editor. These dynamic elements show the insert lists and any editable attributes. Of course, there is also an extensive set of keyboard shortcuts for many commonly used commands. It has been our goal to ensure that the majority of the commonly used documenting tasks can be accomplished from the keyboard alone.

Sidebar

A sidebar along the left side of the application provides access to the major components which make up LegisPro Sunrise. It is here that you can switch among documents, access on-board services such as the resolver and amendment generator, outboard services such as the document repository, and where the primary settings are managed.

A sidebar along the left side of the application provides access to the major components which make up LegisPro Sunrise. It is here that you can switch among documents, access on-board services such as the resolver and amendment generator, outboard services such as the document repository, and where the primary settings are managed.

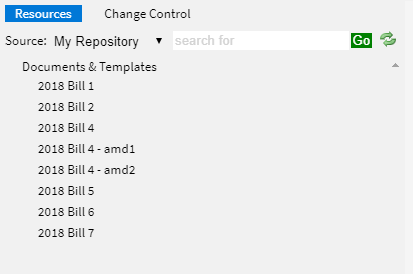

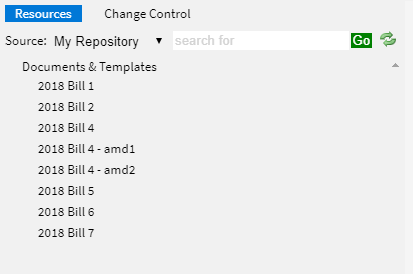

Side Panels

Also on the left side are additional configurable side panels which provide additional views needed for drafting. The Resources view is where you look up documents, work with the hierarchy of the document being edited, and view provisions of other documents. The Change Control view allows the change sets defined by the advanced change control capabilities (described below) to be configured. Other panels can be added as needed.

Advanced features

In addition to the rich capabilities offered for basic document editing, we provide a number of advanced features as well.

Document Management

Document management allows documents to be stored in an XML document repository. The advantage of storing documents in an XML repository rather than in a simple file share or traditional content management system is that it allows us to granularise the provisions within the documents and use them as true reference-able information – this is a key part of moving away from paper document-centric thinking to a modern digital first mindset. An import/export mechanism is provided to add external documents to the repository or get copies out. For LegisPro Sunrise we use the eXist-db XML database, but we can also provide customised implementation using other repositories.

Resolver

Our document management solution is built on the FRBR-based metadata defined by Akoma Ntoso and uses a configurable URI-based resolver technology to make human readable and permanent URIs into actual URLs pointing to locations within the XML repository or even to other data sources available on the Web.

Page & Line numbering

There are two ways to record where amendments are to be applied – either logically by identifying the provision or physically by page and line numbers. Most jurisdictions use one or the other, and sometimes even both. The tricky part has always been the page and line numbers. While modern word processors usually offer page and line numbers, they are dynamic and change as the document is edited. This makes this feature of limited use in an amending system. What is preferred is static page and line numbers that reflect the document at the last point it was published for use in a committee or chamber. We accomplish this approach using a back-annotation technology within the publishing service. LegisPro Sunrise also offers a page and line numbering feature that can be run without the publishing service. Page and line numbers can be display in the left or right margin in inline, depending on preference.

Amendment Generation

One of the real benefits of a digital first solution is the many tasks that can be automated – not by simply computerising the way things have always been done, but by rethinking the approach altogether. Amending is one such area. LegisPro Sunrise incorporates an onboard service to automatically generate amendment documents from changes recorded in the target document. Using tracked changes, the document hierarchy, and annotated page and line numbers, we are able to very precisely record proposed changes as amendments. Of course, the amendment generator works with the change sets to allow different amendment sets to be generated by specifying the named set of changes.

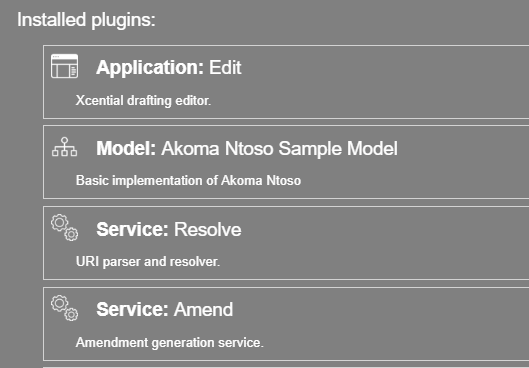

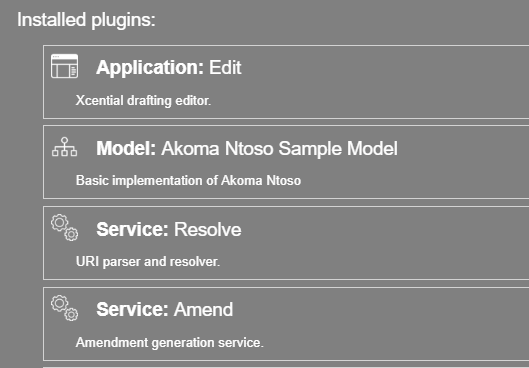

Plugin Support

LegisPro Sunrise is not the first incarnation of our LegisPro offering. We’ve been using the underlying technologies and precursors to those technologies for years with many different customers. One thing we have learned is that there is a vast variation in needs from one customer to another. In fact, even individual customers sometime require very different variations of the same basic system to automate different tasks within their organisation. To that end, we’ve developed a powerful plug-in approach which allows capabilities to be added as necessary without burdening the core editor with a huge range of features with limited applicability. The plugin architecture allows onboard and outboard services to be added, individual commands, menus, menu items, side panels, mode indicators, JavaScript libraries, and text string libraries to be added. In the long term, we’re planning to foster a plugin development community.

Proprietary or Open Source?

There are two questions that always come up relating to our position on standards and open source software:

- Is it based on standards? Yes, absolutely – almost to a fault. We adhere to standards whenever and however we can. The model built into LegisPro Sunrise is based on the Akoma Ntoso standard that has been developed over the past few years by the OASIS LegalDocML technical committee. I have been a continual part of that effort since the very beginning. But beyond that, we always choose standards-based technologies for inclusion in our technology stack. This includes XML, XSLT, XQuery, CSS, HTML5, ECMAScript 2015, among others.

- Is it open source?

- If you mean, is it free, then the answer is only yes for evaluation, educational, and non-production uses. That’s what the Sunrise edition is all about. However, we must fund the operation of our company somehow and as we don’t sell advertising or customer profiles to anyone, we do charge for production use of our software. Please contact us at info@xcential.com or visit our website at xcential.com for further information on the products and services we offer.

- If you mean, is the source code available, then the answer is also yes – but only to paying customers under a maintenance contract. We provide unfettered access to our GitHub repository to all our customers.

- Finally, if you’re asking about the software we built upon, the answer is again yes, with a few exceptions where we chose a best-of-breed commercial alternative over any open source option we had. The core LegisPro Sunrise application is entirely built upon open source technologies – it is only in external services where we sometimes rely up commercial third-party applications.

What does it cost?

As I already alluded to, we are making LegisPro Sunrise available to potential customers and partners, academic institutions, and other select individuals or organisations for free – so long as it’s not used for production use — including drafting, amending, or compiling legislation, regulations, or other forms of rule-making. If you would like a production system, either a FastTrack or Enterprise edition, please contact us at info@xcential.com.

Coming Soon

I will soon also be providing a pocket handbook on Akoma Ntoso. As a member of the OASIS LegalDocML Technical Committee (TC) that has standardised Akoma Ntoso, it has been important to get the handbook reviewed for accuracy by the other TC members. We are almost done with that process. Once the final edits are made, I will provide information on how you can obtain your own copy.

In addition to the Sunrise edition, we offer LegisPro in customised FastTrack implementations of the LegisPro product or as fully bespoke Enterprise implementations where the individual components can be mixed and matched in many different ways.

In addition to the Sunrise edition, we offer LegisPro in customised FastTrack implementations of the LegisPro product or as fully bespoke Enterprise implementations where the individual components can be mixed and matched in many different ways.

Templates allow the boilerplate structure of a document to be instantiated when creating a new document. Out-of-the-box, we are providing generic templates for bills, acts, amendments, amendment lists, and a few other document types.

Templates allow the boilerplate structure of a document to be instantiated when creating a new document. Out-of-the-box, we are providing generic templates for bills, acts, amendments, amendment lists, and a few other document types.

A sidebar along the left side of the application provides access to the major components which make up LegisPro Sunrise. It is here that you can switch among documents, access on-board services such as the resolver and amendment generator, outboard services such as the document repository, and where the primary settings are managed.

A sidebar along the left side of the application provides access to the major components which make up LegisPro Sunrise. It is here that you can switch among documents, access on-board services such as the resolver and amendment generator, outboard services such as the document repository, and where the primary settings are managed.