After the 2014 Legislative Data and Transparency conference, I came away both encouraged and a little worried. I’m encouraged by the vast amount of progress we have seen in the past year, but at the same time a little concerned by how disjointed some of the initiatives seem to be. I would rather see new mandates forcing existing systems to be rethought rather than causing additional systems to be created – which can get very costly over time. But, it’s all still the Wild Wild West of computing.

After the 2014 Legislative Data and Transparency conference, I came away both encouraged and a little worried. I’m encouraged by the vast amount of progress we have seen in the past year, but at the same time a little concerned by how disjointed some of the initiatives seem to be. I would rather see new mandates forcing existing systems to be rethought rather than causing additional systems to be created – which can get very costly over time. But, it’s all still the Wild Wild West of computing.

What I want to do with my blog this week is try and define what I believe transparency is all about:

- The data must be available. First and foremost, the most important thing is that the data be provided at the very least – somehow, anyhow.

- The data must be provided in such a way that it is accessible and understandable by the widest possible audience. This means providing data formats that can be read by ubiquitous tools and, ensuring the coding necessary to support all types of readers including those with disabilities.

- The data must be provided in such a way that it should be easy for a computer to digest and analyze. This means using data formats that are easily parsed by a computer (not PDF, please!!!) and using data models that are comprehensible to widest possible audience of data analysts. Data formats that are difficult to parse or complex to understand should be discouraged. A transparent data format should not limit the visibility of the data to only those with very specialized tools or expertise.

- The data provided must be useful. This means that the most important characteristics of the data must be described in ways that allow it to be interpreted by a computer without too much work. For instance, important entities described by the data should be marked in ways that are easily found and characterized – preferably using broadly accepted open standards.

- The data must be easy to find. This means that the location at which data resides should be predictable, understandable, permanent, and reliable. It should reflect the nature of the data rather than the implementation of the website serving the data. URLs should be designed rather than simply fallout from the implementation.

- The data should be as raw as possible – but still comprehensible. This means that the data should have undergone as little processing as possible. The more that data is transformed, interpreted, or rearranged, the less like the original data it becomes. Processing data invariably damages its integrity – whether intentional or unintentional. There will always be some degree of healthy mistrust in data that has been over-processed.

- The data should be interactive. This means that it should be possible to search the data at its source – through both simple text search and more sophisticated data queries. It also means that whenever data is published, there should be an opportunity for the consumer to respond back – be it simple feedback, a formal request for change, or some other type of two way interaction.

How can this all be achieved for legislative data? This is the problem we are working to solve. We’re taking a holistic approach by designing data models that are both easy to understand and can be applied throughout the data life cycle. We’re striving to limit data transformations by designing our data models to present data in ways that are both understandable to humans and computers alike. We are defining URL schemes that are well thought out and could last for as long as URLs are how we find data in the digital era. We’re defining database solutions that allow data to not only be downloaded, but also searched and queried in place. We’re building tools that will allow the data to not only be created but also interacted with later. And finally, we’re working with standards bodies such as the LegalDocML and LegalCiteM technical committees at OASIS to ensure well thought out world wide standards such as Akoma Ntoso.

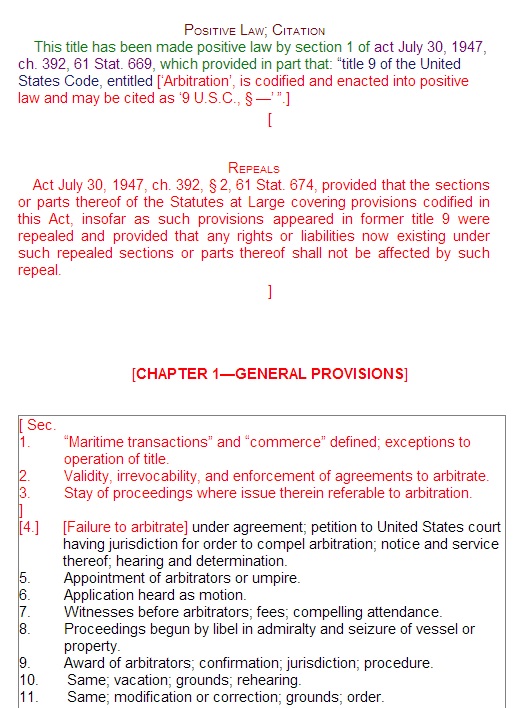

Take a look at Title 1 of the U.S. Code. If you’re using a reasonably modern web browser, you will notice that this data is very readable and understandable – its meant to be read by a human. Right click with the mouse and view the source. This is the USLM format that was released a year ago. If you’re familiar with the structure of the U.S. Code and you’re reasonably XML savvy, you should feel at ease with the data format. It’s meant to be understandable to both humans and to computer programs trying to analyze it. The objective here is to provide a single simple data model that is used from initial drafting all the way through publishing and beyond. Rather than transforming the XML into PDF and HTML forms, the XML format can be rendered into a readable form using Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). Modern XML repositories such as eXist allow documents such as this to be queried as easily as you would query a table in a relational database – using a query language called XQuery.

This is what we are doing – within the umbrella of legislative data. It’s a start, but ultimately there is a need for a broader solution. My hope is that government agencies will be able to come together under a common vision for our information should be created, published, and disseminated – in order to fulfill their evolving transparency mandates efficiently. As government agencies replace old systems with new systems, they should design around a common open framework for transparent data rather building new systems in the exact same footprint as the old systems that they demolish. The digital era and transparency mandates that have come with it demand new thinking far different than the thinking of the paper era which is now drawing to a close. If this can be achieved, then true data transparency can be achieved.

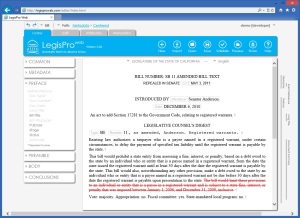

Take a look at the totally contrived example on the left. It’s admittedly not a real example, it comes from my stress testing of the change tracking facilities. But look at what it does. The red text is a complex deletion that spans elements with little regard to the structure. In our editor, this was done with a single “delete” operation. Try and do this with XMetaL – it takes many operations and is a real struggle – even with change tracking turned off. In fact, even Microsoft Word’s handling of this is less than satisfactory, especially in more recent versions. Behind the scenes, the editor is using the model, derived from the schema, to control this deletion process to ensure that a valid document is the result.

Take a look at the totally contrived example on the left. It’s admittedly not a real example, it comes from my stress testing of the change tracking facilities. But look at what it does. The red text is a complex deletion that spans elements with little regard to the structure. In our editor, this was done with a single “delete” operation. Try and do this with XMetaL – it takes many operations and is a real struggle – even with change tracking turned off. In fact, even Microsoft Word’s handling of this is less than satisfactory, especially in more recent versions. Behind the scenes, the editor is using the model, derived from the schema, to control this deletion process to ensure that a valid document is the result.

Input Form

Input Form Validation Results

Validation Results